Having a laff

You are here ⇣

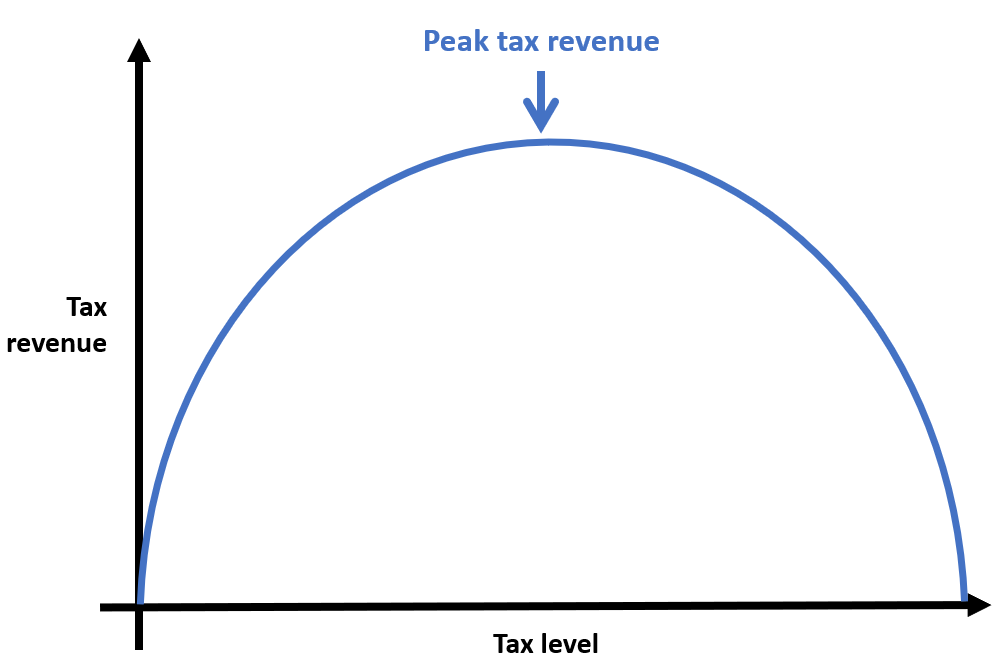

Anyone who has a passing familiarity with neoclassical economics has likely come across the Laffer curve before. It is a simple idea—acknowledged as such even by Arthur Laffer himself—that tax receipts represent their own kind of supply:demand marketplace; manifesting a desire to increase (or decrease as the curve is most often used to justify) the amount of tax the state takes off its citizens, until it reaches a sweet spot.

That spot, which we might think of as Peak Tax Revenue, is where a government is both incentivising the economic growth that “keeping more of your money” promises, while also maximising tax income receipts for public spending.

Of course, it’s worth pointing out that this whole thing is critically reliant on a belief that taxes actually pay for government spending, which—you know—they don’t. But let’s not let that fact get away of our feelings; at least for the timebeing.

The standard mistake most proponents of this way of thinking (read: libertarians) make is to assume we’re always on the right-hand side of the curve when, as should be evident by growing inequality, we’re likely not.

To explain that briefly: If you imagine we increase taxes rightwards, past that ‘peak’ level, what starts to happen is our tax revenue falls. This is ostensibly because people become discouraged from working harder because it would result in them earning (or spending, with consumption taxes) more and—under our (misguided) tax system—therefore paying more tax.

Likewise, the curve implies that if the state doesn’t tax enough, they’re leaving money on the table, because of how many people are flawed losers who will be just as incompetent and lazy regardless of whether they are taxed at 5% or 12%. So, you might as well tax up to the point where you hit the peak.

Of course, if you’re a fan of the ol’ “Job Creator” trope, the worldview you might extract from that is that essentially any tax that tempers initiative beyond the most basic subsistence wage level represents a careening down the back side of the slope towards economic decay. That’s why libertarians love flat tax rates.

I’m not against getting rich.

I do believe we should spend more talking-time on understanding when “enough is enough”, given our various cost-of-living crises, backwards-trending life expectancy, and sad-trombone intergenerational income expectations. But I certainly don’t need us all to receive an identical pay cheque, grey overalls, and a ‘Kumbaya’ song sheet.

So, the problems we face are not nearly as defined by the granular quality of our existing tax system as we might think. For the vast majority of us, our major tax contribution comes from income and, actually, most places have landed on progressive income taxes that account for the range of different incomes fairly well. While there suffer all manner of issues with how much people actually earn and when abatement rates kick in for low-income earners and the like, if you do earn a small amount you’re probably still paying a pretty small amount of net tax. And, if you’re earning a lot of income, you’re probably paying a lot of net tax. So, our problems are less related to the tax on what we earn, and more related to the distribution of power in society—such that, people who are wealthy have drastically more freedom and comfort, but it’s on the basis of wealth more than income. And our existing tax system is not equipped to shift that balance

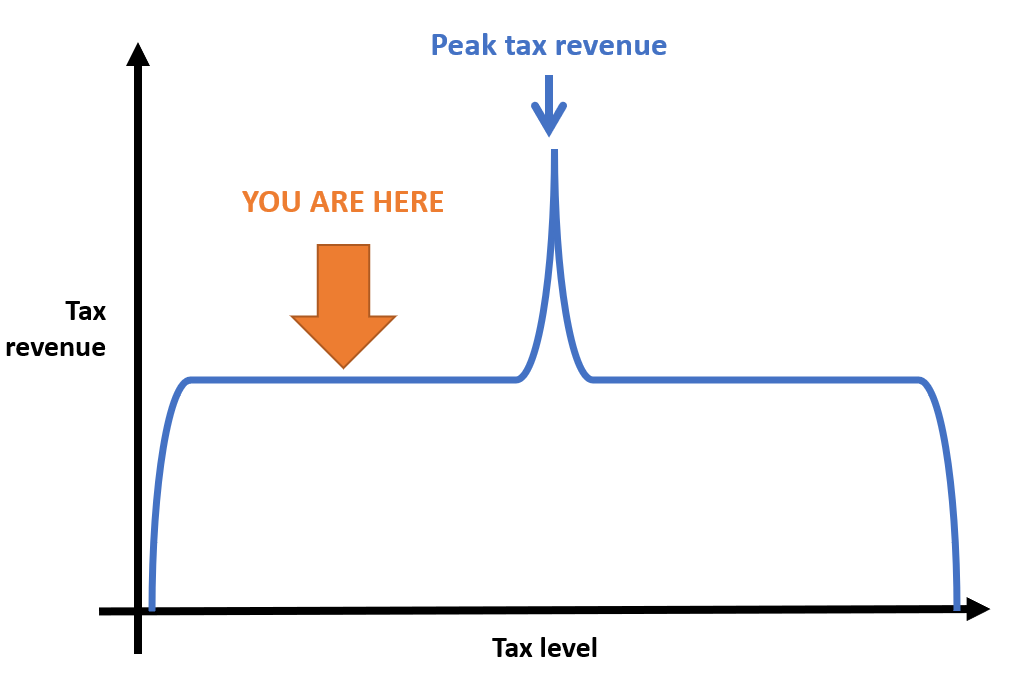

This is all to say, almost any country that continues to rely on progressive income taxes is suffering from a Laffer curve that looks more like this:

This curve is one where the ordinary taxpayers pay too much because the wealthy are not paying enough. It’s one where we have huge gaps where we dis-incentivise productivity, not because the progressive tax levels don’t function as they should, but because income (and consumption) are no longer representative of power and influence in an economy. And the result is, the optimum income tax-bracket-machinations would basically involve extracting as much as possible from a narrow band of people earning good-but-not-spectacular salaries, within the short window of time before they have built up enough wealth to be able to start using accountants, financial advisors, and other “Alternative Universe” trickery and shift past it into the lower-tax paying wealth universe.

What this looks like in practice is people not working, not because they don’t want to do something with their lives but because earning taxable-income will make them worse-off than just staying on welfare. And it looks like anyone with any spare money investing in assets rather than productivity because debt-leveraged-ownership gives them just as good a life, without the extra tax burden of earning more.

This is—it should go without saying—a failing strategy not just for economies but also for governments, principally because everyone who might fall into that ‘peak tax revenue’ bracket is a voter. A large portion of low-earners are so focused on survival that they view voting as the sort of minutiae they don’t have capacity for; and a large portion of the disturbingly-wealthy see voting as a poor substitute for a well-coordinated party donation. While I’m clearly presenting that as a generalisation, it is also true. What it continues to do is leave a decent chunk of the electorally-engaged with a difficult quandary around tax: Do they vote to pay more tax, knowing they’ll get little thanks from disengaged low-earners and will be pitting their single vote against the powerful finances of the wealthy; Or, do they vote for some version of the Centrist status quo and just keep trying to weasel their way up into the ranks of the wealthy themselves?

So, while we might not need everyone to be absolutely equal, we do need to think about how we are redistributing our constantly-changing fortunes, given the way those fortunes are stored and leveraged today is very different from how most people still misunderstand them to work, and how they did work when our tax systems were designed.

There’s a juicy irony in the idea that almost exactly the same people who believe the Laffer Curve makes a genuinely useful contribution to economic planning also don’t realise that a fiat government doesn’t need taxes to pay for anything.

Suffice to say, that means the Laffer curve is what a tax system looks like when people understand what tax is ‘for’.

Which—to clarify—is to motivate certain types of behaviour; not to acquire roads and hospitals.

-T

Thanks, Tim. Safe to say I remain a bit confused, so I'll reread this when my coffee is digested! But - question - so, what if there was, say, no income tax? ...In particular, it certainly does seem that the complicated way Benefits are reduced for people earning additional income - and the policing that has to go on to maintain that - is counterproductive. The checker is not 'producing' anything except the result of their own spending power!! And the marginal amount seems barely worth the effort vs chasing top-end avoiders!!! But if I read the equation correctly, we'd all be chasing what we could earn, if we weren't going to hit a point where it isn't worth it!!! ...

I recall, when I was 23, and a personnel officer at a major UK electronics factory, our setters, fitters & turners got a pay increase. One Sikh man said to me, "We'll need to have another child." Now that was maximising the benefits system! They had it all worked out!!? ....Amazing the things that stick in one's mind half a century later. Especially since I know I'd be financially much better off were I childless. i.e. Over time, the economics of an action also change.