In a couple of my previous newsletters I talked about the bit in the middle.

We do a lot of talking about where rich people get money, and we do a lot of talking about the trauma of inequality. But we rarely spend time talking about how rich people just get richer, and poor people just get poorer… at least, not until we arrive at such a level of inequality that we really need to talk about it.

For better or worse, we live in the Era of Capitalism. We will replace it with something else at some point—just as we shuffled past Mercantilism and Feudalism, and many other ‘isms’, in our long march through history—but, for now, it’s what we’ve got.

I don’t bring that up to get into explicit pros or cons of our current choice of ‘economic system’, but simply to note the combo of ‘capitalism’ and those 'bit in the middle’ mechanics are a dangerous mix—if left unchecked.

Remember, the core principle behind capitalism is that money is a kind of voting mechanism, projecting “more of that” or “less of that” signals out into the world; (collectively) getting us the things we want… or, at least, think we want.

However, if there’s anything we all intuitively understand about voting, it’s how pointless it is if it’s not fair.

Of course, we do sometimes bungle it (accidentally or otherwise), and make voting unfair, but principally we understand it’s pretty silly going to the trouble of a ballot if some of the votes inherently have a different value, or if every vote is cast without some level of shared information.

So, for “money voting” (i.e. capitalism) to work, we need to have agreed rules—what a ‘dollar’ is, how it can be spent, who enforces those things, and how they are enforced, what basic needs should first be met, and so on. For example, we tend to take it for granted but ‘freedom’ is one of those rules: The same kind of ‘votes’ I use to buy gummy worms at the corner shop, can equally be used by you to buy milk, or to buy the corner shop itself, or the gummy worm factory and the labour of the workers inside it, or the time and education required to develop a ‘Revolutionary New Gummy Slug™’.

The truth is though, like authoritarian dictators in government elections, people who are best at the ‘game’ of capitalism don’t actually like shared voting rules so much.

They’ll angrily protest and lobby against “planned economies”, then praise Kaizen production techniques and JIT logistics and manufacturing…

They’ll extol the virtues of the ‘free market’ and the ‘invisible hand’, and then hoover up any hint of a patent to barricade themselves against competitors who might “steal” [sic] such life-affirming proprietary genius as the ‘Ability to Buy Stuff Online’…

Good Capitalist Game Players would frankly much prefer it if employees and tenants didn’t complain so much. They’d prefer it if governments butted-out and let them exploit and obscure and concentrate and outsource and trick… because playing the game with their parallel rules results in more money.

Money is the goal of that game.

But capitalism is, in both principle and in practice (for the vast majority of us), not a ‘game’. It is a means of actualisation.

When we have a dollar, we expect it to unlock our lives in predictable and rule-bound ways. We accept the apparent contradiction where that same dollar can both “epitomise freedom”—allowing us to use it in inconceivable ways—and “operate within strict functional boundaries”.

That’s how capitalism should operate. That’s how it would operate for the best of all of us. But, The 99% and The 1% in our economic system are fundamentally different universes: One is where money delivers things we want and need; the other is where money accumulates as a kind of “life score”.

We have plenty of evidence of this. From the periodic research that demonstrates how money, beyond a relatively modest amount, doesn’t make you happier; to our obsession with impractical status possessions (expensive handbags, cars, watches etc that are no more functional than far cheaper alternatives); to the huge investments in unproductivity (the work of long-dead artists, run-down rental housing, web3 start-ups, crypto coins, private space tourism etc).

Were money to operate as intended under capitalism, it would all be being put towards self- and social- actualisation. Innovation and happiness exist, but without there being ‘value’ in excess.

Don’t be confused, sometimes we absolutely need to accumulate money under capitalism—in order to invest in big things; I’m not talking about that kind of accumulation. And, we can’t always spend with 100% effectiveness; there will always be some ‘waste’. However, the ‘pinnacle of capitalism’ should not be successful lobbying to lower your Family Trust taxes, so your Great-Great-Great-Grandson can buy himself a Hover-Bentley® 113 years from now.

Basically, until we can come up with something better, we need to operate capitalism with the same attentive care that allowed it to do all the ‘freedom’, ‘equity’ and ‘pulling people out of poverty’ stuff that we nostalgically continue to give it credit for. And that means getting on the same page again about the rules.

I think I’ve mentioned in the past, I play a little music and have done a little recording. When you walk into a recording studio monitoring booth, you’re surrounded by racks of knobs and switches and lights (or, more likely now, a computer monitor filled with skeuomorphic representations of knobs and switches and lights). Different audio engineers preference different tools, but they all use at least two: A Limiter (or Gate1), and a Compressor.

On the surface, they seem similar. They are both designed to ‘contain’ the sound within a dynamic/volume range defined by: The genre (classical music is generally produced with more dynamic range than pop music); the primary medium of delivery (CD, streaming, high-resolution etc); and comfort (so listeners don’t have to strain to hear it one moment, then block their ears the next).

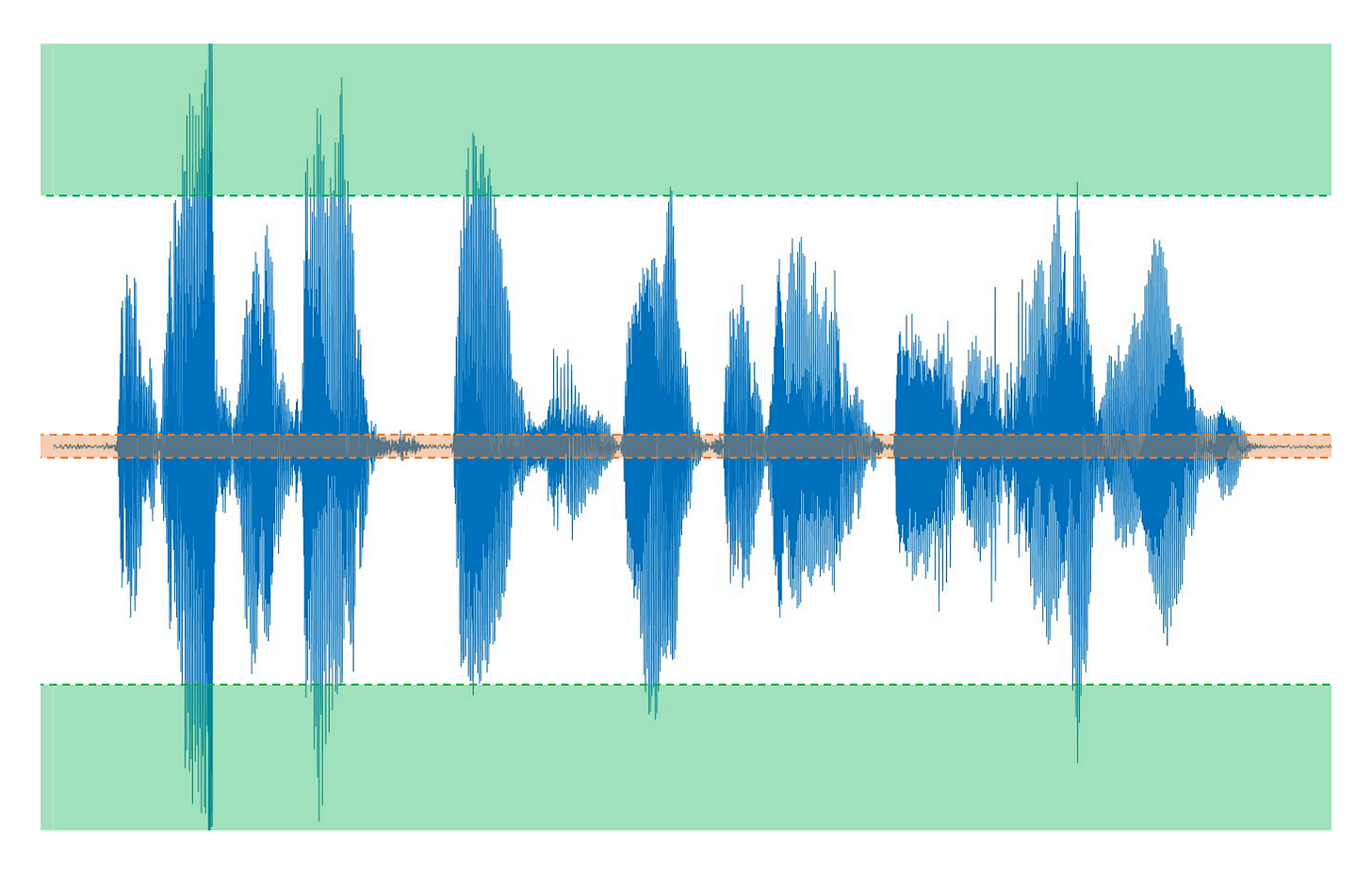

But how they approach this is pretty different. A Compressor reduces the overall dynamic range of an audio track by squashing it from both sides, eliminating loud and quiet surprises, so the whole track plays at a fairly consistent volume level. This makes the track easier to listen to, but it also flattens out some of the authenticity and musicianship.

A Limiter (or Gate), on the other hand, allows the track’s dynamics to be every bit as spirited as their potential allows, until it goes ‘out of bounds’, at which point they are (dramatically) cut off.

These ‘bounds’ represent distortion when it should just be loud, and noise when it should just be quiet. These are not purposeful audio signals, they are unintentional perversions that we remove, in order to deliver the intended experience.2

The rules of capitalism don’t always, but should, operate like a Limiter.

The best of what we’ve achieved in the past 200 years was because ideas were not assuaged—the sharpest minds were not rounded off or ‘compressed’. That’s good.

But much of the worst we’ve experienced in the past 200 years happened when a Limiter was not turned on; the rules we tacitly agree to were not followed and capitalism stopped stalking democracy.

In spite of my occasional facetiousness about it—and in spite of the fact that we now know wealth confers a monstrous advantage upon its havers—no one just trips-and-falls into being a billionaire. They scratch and claw and fight dirty. They, very intentionally, extirpate from themselves the ability to relate to ‘normal human experience’:

A billionaire might imagine their quest for great wealth as a worthy challenge—a goal detached from the reach or influence of their bank balance—but, to rise to that challenge, they still must lean in hard to the very worst selfish human impulses.

I’ve interchangeably used the billionaire synonyms “ambitious” and “asshole” throughout this series because, as philanthropic or friendly as they may be, there’s no getting around the fact that accumulating money like that requires you to crap on a bunch of people.

In essence, operates outside limits.

And, to be explicit, someone living in desperate poverty is also operating outside the limit.

Both of these groups of people need help to bring their ‘excess’ back into the folds of capitalism and society.

When you listen to a well-mastered audio track it sounds effortless.

People spend thousands on high-end headphones and audio systems in order to make their listening experience as authentic as possible. But what they really want to hear through those open-back, neodymium-driven, balanced-interconnect headphones is a sound that delivers the artist’s intent into their ears as conspicuously as possible.

It seems like those are the same thing, but they are not.

A real ‘authentic’ experience is the sound of the guitar tech shuffling around on the edge of the stage, trying to fix the electrical ground-loop-hum in the foldback speakers—which, incidentally, have the distracting keyboard riff turned way down in the mix so it doesn’t mess with the lead singer’s pitching—and the dry snare drum sound is leaking into the bass player’s vocal mic, and there’s no stereo chorus effect on the guitar yet, and the reverb and autotune on the vocals aren’t dialed-in right… The authentic sound is nothing like what an engineer gives you, or the artist wants you to hear, because it’s harder to listen to and just not as good.

So, we apply things like Gates to suppress the interference in the signal cables, and Limiters to prevent that screaming guitar feedback from actually destroying your speakers or ears. We are not squashing creativity with these things, we’re making it accessible to the audience, and thus empowering the creatives.

Look, I hope it’s clear, I’m not outright dissing capitalism. Under the constraints of our current legal, technical, and social frameworks, being somewhat rich is ok; having some gap between rich and poor is ok. As things stand, there’s undoubtedly some amount of money that works to motivate the creation of new things. There’s also undoubtedly some amount of inequity that succinctly demonstrates that we “reward effort”, so our most ambitious and clever individuals go on cleverly investing in our collected human endeavour.

But, people should not live in the noise, and neither should they live in the distortion. That may be the tendency of capitalism, but it was never the intent of capitalism.

This evokes two important ideas: First, for capitalism to actually work at its best, knobs need to be turned until lives are maximised, without the waste of distortion and noise. And, second, if you are a dyed-in-the-wool-capitalism defender, desperately worried about “Commies” and the “Woke Socialist Soy Boys” coming for ‘your’ economic system, at least try to understand what it is you’re fighting for.

Speaking about ignorance, we’re taking a road trip into the Alternative Universe of Wealth next time, to give you a taste of how the 1% live…

-T

A Gate is not strictly the same as a Limiter, but they serve similar aims. A Gate cuts low-level sounds (like static or hiss), while a Limiter cuts high-level sound (like a sudden bang or crash)

I’ve simplified this to make my point. Of course, usually, a Limiter or a Gate will be applied more gently than I’ve implied… think of it like a progressive tax system where the portion of your income that is taxed increases as your income increases. It’s also worth pointing out—if it’s not obvious—sometimes some noise and distortion are deliberately included for artistic reasons. But, even then, the audio is usually limited/gated somewhat to suit the delivery medium.