Interesting behaviour

103

This is the 3rd part of a series about where the value of money comes from, and how it’s important we don’t let its tendency to drive behaviours prevent us from benefiting from some of the incredibly useful things its actual mathematical basis allows for.

You should read part 101 and part 102 if you haven’t already, as they’re worthwhile preloading to get you buzzed for this one.

One thing about behaviour is, even if it is a reaction to something that isn’t “real”, the behaviour itself can cause real benefit or harm: If you performatively yell “fire” in a crowded space, there’s a real chance people will end up getting hurt in the—imagined—panic. Likewise, if ambitious politicians and their constituents believe they can’t spend money on all their pet projects (because they’d need to tax or borrow to do it) then they invariably behave in a more responsible way and spend on things which do deliver widespread good.

While I’ve spent the last couple of posts blithely dismissing money as anything more than a nifty trick for economic ease, it’s clear that the behaviours based on our beliefs about money are powerful, useful, and have very real outcomes. So, I don’t want to leave you with the impression that money is only a party trick, and that building 25-lane freeways or gold-plated schools comes without any real cost. It’s just a cost that is increasingly borne unevenly. That’s why, today, we need to talk about inflation: what it is and what it isn’t, and why solving it using economics is now proving much easier said than done.

There’s an important idea at the core of this entire series, which is that money isn’t a thing—a commodity, if you like—but is rather an invitation for inclination. That sounds cryptic, but it’s simpler than it seems: money invites you to make choices, giving you permission to dream or envision beyond your immediate capabilities. Even if we choose to believe the persistent myth that money evolved as an ‘easier alternative to barter’, to save having to trade goats for eggs, or seeds for roof thatching, it still served that purpose. It expands your mindset, allowing you to believe—despite having just goats and not seeds—that you could, still, have roof-thatching. It invited humans to aspire for things, to preference things, and to amass for things. It basically opened our eyes to choice.

You’ll no doubt notice that means money opens us up to new behaviours. That’s true, and it is the psychological side that the study of economics was made for. But none of that changes the fact that money itself needs to be manufactured somewhere and imbued mathematically with value because, without that, it is no one’s behaviour to hand over goats for a piece of paper that they then can’t exchange for anything else.

I’ve written multiple times about inflation, and the good and bad:

Today, through the varied but interrelated lenses of real tension around population, productivity, inequality, and possibile alternatives to State money, I want to insert some math into it.

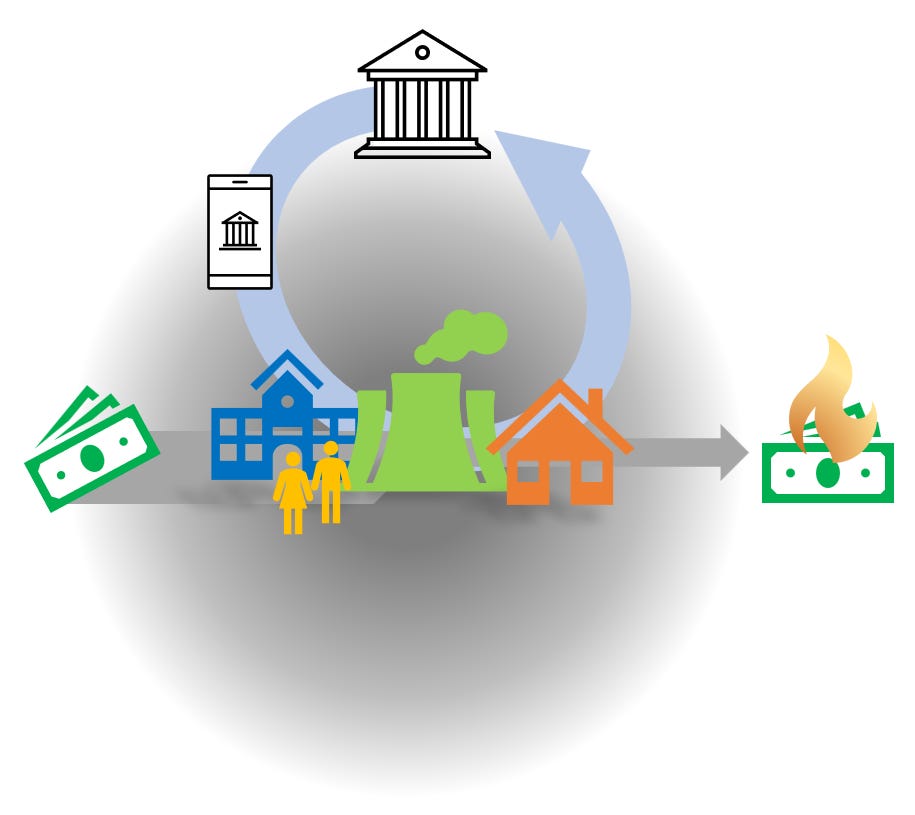

Let’s put some money into our economy:

This diagram should be broadly familiar to you now. The grey State money flows into the economy to commission the doing of ‘public good’. While most of it stays in the economy, cycling around inside it, every citizen is forced (using the power and violence of the State) to pay some amount of it back as a “tax”. Even though the taxed money actually is just getting destroyed, that simple coercion of it—from everyone— ensures all participants in the economy are incentivised to either:

Give away what is not needed to pay taxes in exchange for other desirable goods and services; or

Offer appealing goods and services to those with money until you have (at least) enough to pay your own requisite taxes.

That gives money an inherent value across the economy. So, once you’ve established that base, you can add in other money creators—commercial banks—with one caveat: They can create money for a much wider range of uses (i.e. not just public good), however any money they create needs to be returned back to them in full; it can’t remain in the economy, like the State-created money can.

There are mechanisms to signal, and act upon, how effectively the maths of this all is working—bonds and central banks, as discussed last time—but they are actually not overly important for now.

So, with that re-established, we now have a new item in our diagram: Let’s call it something catchy like, the “Money Ball”. This is that hazy grey ball underneath our economy in the diagram.

You’ll remember the formula:

Money - Productivity = Inflation

The grey ball represents the ‘Money’ bit of that equation. It expands and deflates as a result of basically three things:

Money created by the State: For public good

Money created for citizens and other currency users (like, for example, importers from other States) by commercial banks: For a dynamic economy

Taxes paid to the State: To maintain the value of money.

It can be hard to get your head around this because it happens over large time scales and geographies, but essentially, the more money in an economy—either dormant or active—the larger that ball grows.

It’s worth noting that a growing Money Ball can result from several good things:

An appealing economy that is attracting immigration from other States, and therefore simply increasing the (tax-coerced) population

Dynamic and innovative labour and capital performance, creating an attractive lending environment for commercial banks (basically, “good ROI1” in corporate-speak)

A proactive State that is building infrastructure and modelling strong wages, delivering citizens empowering welfare payments or something like a Universal Basic Income.

And, of course, it can equally result from some less-good things:

Monopoly or other cartel price increases

Equity loans from unproductive asset hoarding

Irresponsible or poorly-regulated commercial bank lending

Counterfeiting.

Remember, at this point, we’re not talking about money being spent, just money that the commercial banks haven’t yet recovered, and the State hasn’t taxed.

In that context, we can broadly think of inflation as an absorption problem. But, as the formula above makes plain, a lack of absorption can be caused by an insufficient sponge just as easily as too much substance.

There are loads of ways you might define “inflation”. There are certainly ways that governments measure it, with indexes tracking the price of a basket of things. And it’s worth reiterating that not all inflation is bad—as you’ll see. However, because the economy is effectively a sealed box, it’s worth understanding that, mathematically, inflation is really just the power of money—that is, ‘money’, the concept that drives behaviour, or the ‘invitation for inclination’—being reduced.

Let’s see if I can give you an example. One thing that is true about inflation is that it is bad for anyone using money, but good for everyone who owns an asset that can stand in, or be exchanged for, money. Imagine you had $100 to spend on coffee. You might buy 20 coffees worth $5 each. But, if coffee prices increase by, say, 30% that same money would only buy 15 coffees.

This is rough if you’re a coffee fan with money. But, let’s imagine you instead had purchased a 20-coffee loyalty card with your $100. You’ve now inclined the behaviour of that money to coffee buying; however, the card you paid $100 for is also now effectively worth $130 if you were going to buy those 20 coffees anyway.

This works on bigger, broader things as well. If groceries, energy, childcare, housing, and transport all increase in price, you invariably benefit more from owning a house with a veggie garden and solar panels within walking distance to useful locations, compared to having money just sitting in a bank account.

That is, incidentally, why some amount of price rising (inflation) is government policy almost everywhere. It encourages you to spend money today, rather than save it only to have it deliver less buying power. They just have to be aware of the risk of prices rising at such a high rate that no one saves at all anymore (“high inflation”). At that point, citizens inside an economy lose the ability to do big things that require saving-up for.

Governments have traditionally managed this fine balance through some combination of tax and, increasingly, the central bank interest rate mechanism we talked about last time. Practically, most of the money being poured into a modern economy is from commercial bank money creation now, so interest rate control is considered a vital spigot for any democratic State that doesn’t want to do the hard political work of justifying higher public spending (that is, more government “involvement”), or higher taxes (more government “theft”).

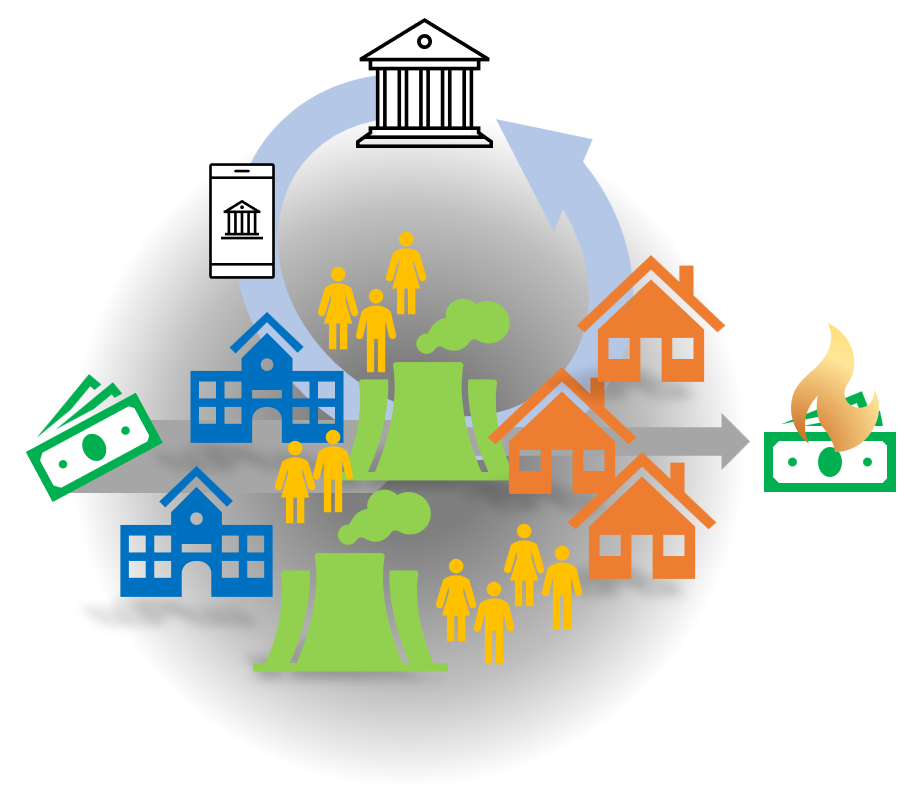

Still, chances are you’re thinking, “Hold on. The newsperson just told me inflation was back under control?” Why are we still hearing about (and experiencing) a ‘cost of living’ crisis? This is what it looks like when the Money Ball fills up with things that we have ceded State-money-supply control over—private assets, privatised services, corporate consolidation, political funding opacity, pork barrelling or other casual corruption—such that simply existing costs more, but in weird, obscure, and indirect ways that the typical consumer price/inflation index can’t track. That’s how we can be feeling real pain (cost of living), but simultaneously being assured the ‘data’ tells us it’s not happening (CPI inflation).

And the way politicians are managing it, it’s not going away

The central bank interest rate spigot doesn’t work like it once did. Wealth inequality, and the overwhelming dominance of ‘assets’ in the Money Ball, now mean that there is a parallel economy operating that is nonplussed by these old-school mathematical mechanisms. This is what I’ve previously referred to as the Alternative Universe of Wealth. A simple example might be how someone with equity built up in a basically unproductive but “commercial-bank-friendly” asset can go into their bank and borrow money at a low interest rate. That instantly increases the size of the Money Ball, yet adds nothing to the economy: The asset they borrowed against is still just delivering the same tangible value, but now there’s extra money as well. By definition, the commercial bank is not obligated to ensure the spending results in public good, only that they’ll eventually get the money back, so that new money might just be spent overseas or on other unproductive assets, or on something like private schooling or healthcare, which suck shared talent, resources, and competition away from the wider public—essentially crowding out the public good mandate of the State.

This borrower could spend their new money on building new productive factories, but why would they, when the return on just owning more assets is as good or better, with less risk, effort, or tax? If you borrow against equity in your own house, to bid up the price on another existing house, you are supporting a rising housing market (which you’re part of) as well as aquiring another leveragable asset—all while adding no new productivity to the economy. Which is all to say, housing is not ‘unproductive’ per se, but—given shelter is an essential to life—the portion of housing value that overprices it relative to the buying capacity of an average citizen, is.

The clearest example of this is actually in the way “inflation hedging” assets like crypto and gold behave now. These were originally things with value behaviourally-established on the basis of scarcity and usefulness. That is, there was a (theoretically) productive reason for them to be valuable. But, of course, the vast majority of their markets are just based on trading them as paper assets now. Essentially, none of the Bitcoin investors ever mined a coin to begin with, and crypto that has emerged since doesn’t even require mining at all. Likewise, gold investors aren’t putting it to use in tooth-fillings or circuit boards. The fact that the value of these things is not measured in time, GPU cycles, wedding rings, or audio plugs coated, but rather in the same US-dollars that your local rubbish collector props up the value of with their income tax, should clue you into what they really are.

We can picture this. An economy that is asset-heavy ends up with an enormous Money Ball; completely out of scale with the actual economy. Assets are overpriced because they are owned in lieu of money. Basically, these are ‘loyalty cards’ that underprice the lifestyles of wealthy asset owners compared to the actual economic reality for the rest of us. You might say, “Well, but that’s exactly what the central bank interest rate mechanism is supposed to control”, but that only works on people who need to leverage a meaningful portion of their assets to buy things: If you own a $500,000 house and want to borrow 10% of its value to buy a car, high interest rates are going to slow you down. On the other hand, if your neighbour has a $5,000,000,000 asset portfolio and wants to borrow again 0.1% of it to buy your house, then the interest rate is basically neither here nor there.

Of course, if interest rates do come down, that gives the wealthy even more flexibility to borrow and scoop up more assets. The point is, once you own enough that you’re basically isolated from interest rate rises, you are free to dip in and out of the real economy—the one valued in tax obligations—as and when you like. It’s all upside.

This is all to say, the central bank interest rate control is not working as it should because of the number of coffees already banked on loyalty cards. This is not a problem with the existence of the loyalty cards exactly, but rather the scale.

That might be a glib statement, but it is a real problem. The mechanisms that cause money to operate in useful ways don’t hold together when so much of it is effectively immune from participation.

This is why understanding that tax establishes the value of money is so important, and loops us right back to my first piece in this series.

I’ve increasingly concluded that the misunderstanding of this is what has made income tax such a quaint idea. For a while, taxing income was a sensible and effective way to ensure a wide distribution of people were captured by this coercive (but essential) requirement, because basically everyone earned ‘income’. But now, our Money Balls are so dominated by assets isolating a privileged few from contributing to this tax-centred valuation that the core mechanism—the thing a money-issuing-State literally needs to animate little pieces of printed paper and metal tokens into ‘invitations’ which allow their citizens to freely choose roof-thatching, goats, eggs, or unlimited other things—is flailing.

Of course, most politicians and many economists don’t appear to understand this underlying dynamic. Or, more pertinently, their current career success depends on their not understanding it. They still view tax as simply government prioritising their “income” above that of their citizens, and therefore a hindrance to address; and they think of all money creation as a blunt force-multiplier.

But this leads naturally to the idea that we should have both “less taxes” and “more wealth”. And, if you’re following along, you will have already noticed the contradiction.

Specifically, this is why you can only cut taxes so far, NOT because governments need tax money to pay for things, but because cutting taxes undermines the literal value of the money, which, in turn, stalls our inclination to spend it. And that’s the sort of thing that breaks economies.

If simply owning an asset increases your ability to create new money at a rate faster than is possible from being productive, and we also don’t tax assets properly, then workers pay the price to value money for the weighted benefit of asset owners. This is how you create a world of both low ‘inflation’ and a cost-of-living crisis.

And fuck-that patronising ‘Consumer Price Index’ bullshit! If you’re struggling to live a pretty ordinary life week-to-week, and being told by politicians that inflation has come down, so now interest rates need to decrease and then the rich can “fire up the economy” with more house and yacht purchases… It’s almost enough to make you vote for self-interested, socially-destructive assholes who want to tear the whole system down…

The underlying problem has been bubbling for a while, but we’ve gotten away with it for a few decades because economies are big, complex, slow-moving beasts. But with so much money now in unproductive things—second-hand houses, crypto and NFTs, shares with insane P:E ratios, government bonds, and, by extension, all those pension funds governments now insist we need to pour money into to pay “for our future”—the problem is bubbling out into our daily lives.

There are people proposing solutions of course. One you’ve likely heard of is Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), which (rightfully) points out that the State can spend as much as you like—to build public goods—provided the money is soaked up by increased productivity, or (less politically-viable) removed by taxes. Essentially, all they concern themselves with is the inflation from having too much money chasing too few goods.

This is pretty sensible. But I wonder if even a foundation of simply ‘soaking up State money with new productivity’, rather than going right back to the core ‘taxation creates value’, might mean we fail to prevent stored money—the ‘loyalty cards’ if you like—from continuing to grow in value, and therefore continuing to increase our cost of living.

For example, if a modern State spends to build a new hospital right now, there are a bunch of existing private assets (hospital equipment monopolies, land leases, specialist doctors with residential housing portfolios, global construction material supply chains, etc) that will explicitly benefit from that investment. It seems to me that a State, therefore, would have to either spend an impossibly large amount to bypass these problems (new doctor training, local construction materials factories, massive land acquisition schemes, etc); or just be brave enough to pull all those Alternative Universe things back into the same economy as regular taxpayers by taxing wealth and regulating privilege.

It’s worth noticing that all this cost-of-living stuff really kicked off in many countries as interest rates were rising after COVID. Some of it was supply disruption of course, but that actually recovered incredibly quickly. Neoclassical economics would tell us that’s not the way things should have worked; rising interest rates should have reduced spending, reducing the demand for goods and, thus, forcing a reduction in their prices... I don’t want to get too conspiratorial, but it’s interesting to notice that did not—and is not—happening.

The irony is that interest rate changes are instead starting to work in ways that are opposite to how traditional economists say they should. Because such a large portion of our Money Ball consists of assets that are sheltered from the fundamental maths that makes the economy work, they are increasingly likely to do what a common idiot thinks they’ll do instead. To a commoner, increasing interest rates sounds like it will just make things cost more: If you rent out a building and your mortgage is going up, you’re going to increase the rent you charge. If you have to borrow to buy a big ship or build a big oil drill or whatever, you’re going to charge more to cover the cost of your interest payments. But economists, starting with Milton Friedman and the Chicago school, assured us the opposite happens. They said, increasing interest rates will slow down borrowing and reduce the amount of money in the economy because the effective cost of that money has gone up. There’s a logic to that, but only when most of the economy is borrowing, spending, and building on productive things. It falls apart when much of the economy is simply hoarding and leveraging unproductive capture. We have plenty of goods to buy, so it’s not a problem of too much money chasing too few goods anymore; it’s a problem of too much ability of companies to hike prices, knowing the Alternative Universe protects them from any economic damage.

The frustration is, now, this cost-of-living problem seems perpetual, and economists are confused about why their models don’t work anymore. So, they are blaming governments for “printing too much money” or not delivering enough business-friendly policies. Only those things won’t solve the problem. Like most populist politics, they simply kick the can down the road—and not even very far! Once you understand what money is, you can’t help but realise inadequate, two-tier, tax schemes and deregulation were eventually always going to metastasise into the poles of growing homelessness and record highs on the sharemarket. We’re pretty deep into it now, so while we don’t have an exact historical parallel from which to know what comes next, there’s likely some interesting behaviour on the horizon.

-T

Return on Investment.

Excellent article makes things much clearer

But what to do? What to do? Spend like there's no tomorrow? Save like there's an arctic winter coming? try to become self sufficient with water tanks, solar panels? Work or retire? grow vegetables or buy them? Or put my head in the sand and eat plastic till it's coming out of my ears?